HHLA History

HHLA History

Since our founding in the year 1885, we at HHLA have been shaping the logistics of the future: From the first forklifts to automated transport vehicles to the digital networking of the entire logistics chain – innovation was and is our drive.

Today, as a European network logistics provider, we connect people, goods, and markets with efficient and environmentally friendly technologies. Our history is the foundation for the future – and we continue to drive progress forward.

Discover defining moments from HHLA’s past, and our vision for the future – all in our anniversary magazine “World in Motion.”

Today

Today

The Power of Networks

Als europäischer Netzwerk-Logistiker schaffen wir bei der HHLA die Voraussetzungen dafür, dass unser Alltag und unsere Wirtschaft zuverlässig laufen. Gemeinsam mit unseren Kunden und Partnern machen wir Logistik

resilient, effizient und nachhaltig. Dafür setzen wir auf intelligente Lösungen und die Kraft unserer Netzwerke.

2024

Erweiterung unseres intermodalen Netzwerks

Unser intermodales Netzwerk wächst: Mit der Integration der Roland Spedition, dem größten inhabergeführten Anbieter klimafreundlicher Hinterlandtransporte in Österreich, stärken wir unsere intermodalen Verbindungen und

erweitern unsere Präsenz in Zentraleuropa.

2022

Wasserstoff-Innovationscluster

Wir bei der HHLA setzen auf die Erprobung von Wasserstoff als alternativer Energieträger und gründen das Clean Port & Logistics Innovationscluster, um zukunftsweisende Lösungen für eine nachhaltige Logistik zu

entwickeln.

2021

HHLA Next: Zukunft gestalten

Mit der Gründung von HHLA Next, unserer Innovations- und Venture Building-Einheit, fördern wir die Digitalisierung und Nachhaltigkeit in der maritimen Logistik. Wir investieren in zukunftsweisende Start-ups wie HHLA Sky,

und in erfolgreiche Unternehmen wie den Automatisierungsspezialisten iSAM.

2020

Ein wegweisendes Projekt für die Zukunft

Bis heute läuft am Container Terminal Burchardkai (CTB) das größte Brownfield-Projekt der Branche. Wir entwickeln den größten Containerterminal Deutschlands schrittweise im laufenden Betrieb zu einem hochmodernen,

automatisierten und effizienten HHLA-Container-Hub in unserem europäischen Netzwerk.

2018

HHLA erweitert Netzwerk im Baltikum

Wir bauen unsere Position im Baltikum durch die Übernahme von Transiidikeskuse AS, dem größten Terminalbetreiber Estlands, aus. Unser Terminal HHLA TK Estonia erweitert unser Netzwerk in der Region und stärkt unsere

Stellung im internationalen Hafenmarkt.

2015

Weltkulturerbe Speicherstadt

Die von HHLA Immobilien verwaltete Hamburger Speicherstadt wird zusammen mit dem benachbarten Kontorhausviertel von der UNESCO zum Weltkulturerbe ernannt.

2005-2007

Mit neuem Namen an die Börse

Die HHLA trägt seit 2005 den Namen "Hamburger Hafen und Logistik AG" und bereitet sich damit auf den Börsengang vor. Am 2. November 2007 werden erstmals 30 Prozent unseres Grundkapitals an der Börse gehandelt.

2004

Großes Ausbauprojekt am HHLA Container Terminal Burchardkai

Mit dem Startschuss für mehr Produktivität und nachhaltigere Prozesse bauen wir seit 2004 den gesamten HHLA Container Terminal Burchardkai (CTB) in Hamburg bei laufendem Betrieb umfassend um. Das größte

Brownfield-Projekt der Branche läuft bis heute und sichert die Zukunftsfähigkeit des CTB durch modernste Technologien und nachhaltige Lösungen.

2002

Eröffnung des HHLA Container Terminal Altenwerder

Nach nur vier Jahren Planungs- und Bauzeit eröffnen wir den HHLA Container Terminal Altenwerder (CTA) in Hamburg mit einem großen Festakt. Mit seinem hohen Automatisierungsgrad ist der CTA wegweisend für den

Containerumschlag. Außerdem zählt er zu den nachhaltigsten Anlagen seiner Art.

2001

Container Terminal Odessa

2001 erhalten wir die Konzession zum Betrieb des HHLA Container Terminal Odessa (CTO) in der Ukraine und stärken damit unsere Präsenz in der Region.

1996

Tollerort: Unser zweiter Containerterminal in Hamburg

Wir erwerben den Container Terminal Tollerort (CTT) von der Gerd Buss Lager- und Speditionsgesellschaft und erweitern damit unsere Kapazitäten im Hamburger Hafen.

1994

Umbau der Speicherstadt

In der Speicherstadt wandelt HHLA Immobilien die ersten Speicherblöcke, die längst nicht mehr als Warenlager genutzt werden, in moderne und attraktive Büroräume um.

1992

Engagement in der Ukraine

Mit einem Beratungsprojekt unserer Tochterfirma Hamburg Port Consulting (HPC) in Odessa im Rahmen eines EU-Programms beginnt unser Engagement in der Ukraine.

1991

Aufbau von Bahnverkehren nach Ost- und Mitteleuropa

Die auf intermodalen Transport spezialisierten Logistikdienstleister Polzug und METRANS, unsere später fusionierten HHLA-Bahntöchter, organisieren die ersten Schienenverkehre nach Osteuropa und wachsen dynamisch.

1982

Alleskönner O'Swaldkai

Hamburg erhält eine Mehrzweckanlage: den HHLA Terminal O'Swaldkai, der alle Anforderungen des Hafenumschlags erfüllt. Mit RoRo-Rampen (RollOn-RollOff), Schwerlastkränen und Containerbrücken ist der Terminal bestens

ausgestattet.

1976

Gründung von Hamburg Port Consulting

1976 gründet die HHLA die Hamburg Port Consulting (HPC), um unsere Expertise weltweit anderen Häfen zugänglich zu machen. Bis heute unterstützt HPC global Hafenbetriebe mit fundiertem Wissen und innovativen Lösungen.

1975

Beteiligung an Hansaport

Die HHLA erwirbt 49% der Anteile an der Hansaport Hafenbetriebsgesellschaft. Die Anlage für Kohle und Erze bewegt heute bis zu 15 Prozent der gesamten Umschlagmenge im Hamburger Hafen.

1972

Erste Tochterunternehmen der HHLA

Seit 1972 organisiert der CTD Container-Transport-Dienst als erste HHLA-Tochtergesellschaft Hinterlandtransporte und Hafenumfuhren. Mit der Zeit kommen immer mehr Tochterunternehmen hinzu.

1966

Die rollende Fracht erreicht den Hamburger Hafen

Wir wandeln eine ehemalige Rollanlage der britischen Armee zur ersten Anlaufstelle für RoRo-Fracht (RollOn-RollOff) im Hamburger Hafen um und setzen damit einen Meilenstein in der Logistik.

1961

Innovative Fruchtlogistik macht Hamburg zum Fruchthafen

Wir errichten den modernsten Bananenschuppen Europas. Mit Elevatoren gelangen die Bananen wettergeschützt in die Lagerhallen. Weitere Innovationen folgen und machen Hamburg zu einem der führenden Fruchthäfen weltweit.

1952

Moderne Gabelstapler revolutionieren die Hafenlogistik

Bis 1952 dominierten Sackkarren die Hafenarbeit. Mit dem Einsatz moderner Gabelstapler für Stückgüter – Schwergutstapler gab es bereits – wird bei der HHLA nun schneller und effizienter gestapelt.

1945

Wiederaufbau von Hafen und Speicherstadt

Im Zweiten Weltkrieg wurden große Teile des Hamburger Hafens und der Speicherstadt zerstört. Die HHLA startet nun ein gigantisches Wiederaufbauprojekt – ein Schlüsselmoment für Hamburgs Hafen!

1935-1939

HFLG übernimmt Kaiverwaltung und wird zur HHLA

Um Defizite der staatlichen Kaiverwaltung mit den Überschüssen der HFLG, unserer Vorgängerin Hamburger Freihafen-Lagerhaus-Gesellschaft (HFLG), auszugleichen, fusionierten beide Einrichtungen. 1939 entsteht daraus die

„Hamburger Hafen- und Lagerhaus-Aktiengesellschaft“ – die heutige HHLA.

07.03.1885

Gründung der HFLG und Bau der Speicherstadt

Mit der Gründung der Hamburger Freihafen-Lagerhaus-Gesellschaft (HFLG), unserer Vorgängerin, beginnt der Bau der Speicherstadt. Bis heute handelt es sich um den größten Lagerhauskomplex der Welt.

1866

Gründung der Kaiverwaltung und Eröffnung des Sandtorkais

Mit der Eröffnung des Sandtorkais beginnt in Hamburg der moderne Umschlag direkt an der Kaikante. Für den Hafenbetrieb wird die Kaiverwaltung gegründet, mit der wir als HHLA später fusionieren.

Heute

Heute

The Power of Networks

Als europäischer Netzwerk-Logistiker schaffen wir bei der HHLA die Voraussetzungen dafür, dass unser Alltag und unsere Wirtschaft zuverlässig laufen. Gemeinsam mit unseren Kunden und Partnern machen wir Logistik

resilient, effizient und nachhaltig. Dafür setzen wir auf intelligente Lösungen und die Kraft unserer Netzwerke.

2024

Erweiterung unseres intermodalen Netzwerks

Unser intermodales Netzwerk wächst: Mit der Integration der Roland Spedition, dem größten inhabergeführten Anbieter klimafreundlicher Hinterlandtransporte in Österreich, stärken wir unsere intermodalen Verbindungen und

erweitern unsere Präsenz in Zentraleuropa.

2022

Wasserstoff-Innovationscluster

Wir bei der HHLA setzen auf die Erprobung von Wasserstoff als alternativer Energieträger und gründen das Clean Port & Logistics Innovationscluster, um zukunftsweisende Lösungen für eine nachhaltige Logistik zu

entwickeln.

2021

HHLA Next: Zukunft gestalten

Mit der Gründung von HHLA Next, unserer Innovations- und Venture Building-Einheit, fördern wir die Digitalisierung und Nachhaltigkeit in der maritimen Logistik. Wir investieren in zukunftsweisende Start-ups wie HHLA Sky,

und in erfolgreiche Unternehmen wie den Automatisierungsspezialisten iSAM.

2021

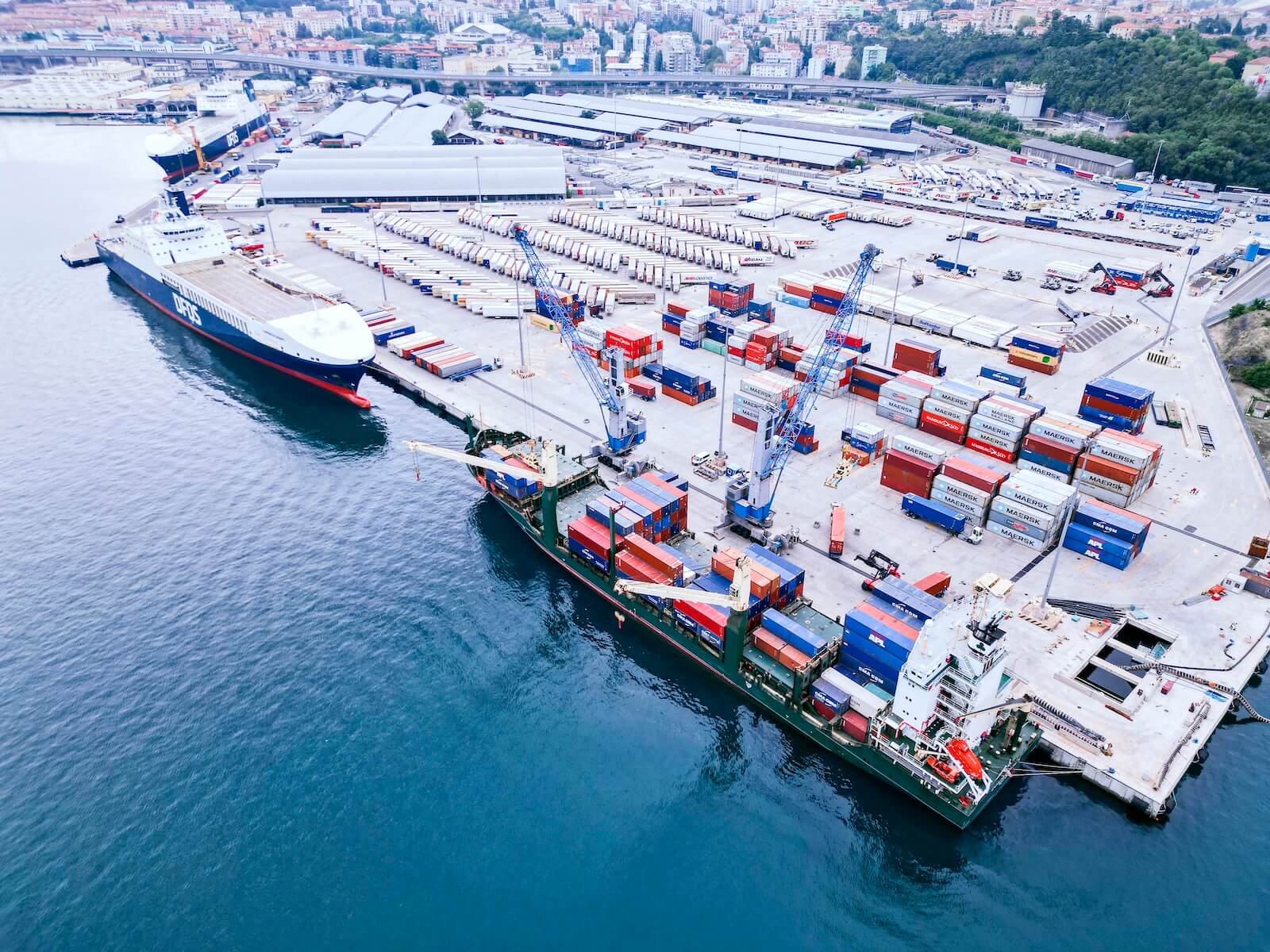

HHLA erweitert Netzwerk in Richtung Adria

Wir stärken unsere Präsenz in der Adria-Region, indem wir den Mehrzweckterminal Piattaforma Logistica Trieste erwerben, der nun unter dem Namen HHLA PLT Italy firmiert. Mit diesem Schritt bauen wir unsere

Logistikverbindungen in Südeuropa gezielt weiter aus.

2020

Ein wegweisendes Projekt für die Zukunft

Bis heute läuft am Container Terminal Burchardkai (CTB) das größte Brownfield-Projekt der Branche. Wir entwickeln den größten Containerterminal Deutschlands schrittweise im laufenden Betrieb zu einem hochmodernen,

automatisierten und effizienten HHLA-Container-Hub in unserem europäischen Netzwerk.

2018

HHLA erweitert Netzwerk im Baltikum

Wir bauen unsere Position im Baltikum durch die Übernahme von Transiidikeskuse AS, dem größten Terminalbetreiber Estlands, aus. Unser Terminal HHLA TK Estonia erweitert unser Netzwerk in der Region und stärkt unsere

Stellung im internationalen Hafenmarkt.

2015

Weltkulturerbe Speicherstadt

Die von HHLA Immobilien verwaltete Hamburger Speicherstadt wird zusammen mit dem benachbarten Kontorhausviertel von der UNESCO zum Weltkulturerbe ernannt.

2012

Intermodale Ausrichtung

Durch eine Neustrukturierung übergibt die Deutsche Bahn der HHLA ihre Anteile an den auf intermodalen Transport spezialisierten Logistikdienstleistern METRANS und Polzug. Wir richten damit unsere Aktivitäten gezielt

auf leistungsfähige Bahnverbindungen ins Hinterland aus.

2005-2007

Mit neuem Namen an die Börse

Die HHLA trägt seit 2005 den Namen "Hamburger Hafen und Logistik AG" und bereitet sich damit auf den Börsengang vor. Am 2. November 2007 werden erstmals 30 Prozent unseres Grundkapitals an der Börse gehandelt.

2004

Großes Ausbauprojekt am HHLA Container Terminal Burchardkai

Mit dem Startschuss für mehr Produktivität und nachhaltigere Prozesse bauen wir seit 2004 den gesamten HHLA Container Terminal Burchardkai (CTB) in Hamburg bei laufendem Betrieb umfassend um. Das größte

Brownfield-Projekt der Branche läuft bis heute und sichert die Zukunftsfähigkeit des CTB durch modernste Technologien und nachhaltige Lösungen.

2002

Eröffnung des HHLA Container Terminal Altenwerder

Nach nur vier Jahren Planungs- und Bauzeit eröffnen wir den HHLA Container Terminal Altenwerder (CTA) in Hamburg mit einem großen Festakt. Mit seinem hohen Automatisierungsgrad ist der CTA wegweisend für den

Containerumschlag. Außerdem zählt er zu den nachhaltigsten Anlagen seiner Art.

2001

Container Terminal Odessa

2001 erhalten wir die Konzession zum Betrieb des HHLA Container Terminal Odessa (CTO) in der Ukraine und stärken damit unsere Präsenz in der Region.

1996

Tollerort: Unser zweiter Containerterminal in Hamburg

Wir erwerben den Container Terminal Tollerort (CTT) von der Gerd Buss Lager- und Speditionsgesellschaft und erweitern damit unsere Kapazitäten im Hamburger Hafen.

1994

Umbau der Speicherstadt

In der Speicherstadt wandelt HHLA Immobilien die ersten Speicherblöcke, die längst nicht mehr als Warenlager genutzt werden, in moderne und attraktive Büroräume um.

1992

Engagement in der Ukraine

Mit einem Beratungsprojekt unserer Tochterfirma Hamburg Port Consulting (HPC) in Odessa im Rahmen eines EU-Programms beginnt unser Engagement in der Ukraine.

1991

Aufbau von Bahnverkehren nach Ost- und Mitteleuropa

Die auf intermodalen Transport spezialisierten Logistikdienstleister Polzug und METRANS, unsere später fusionierten HHLA-Bahntöchter, organisieren die ersten Schienenverkehre nach Osteuropa und wachsen dynamisch.

1982

Alleskönner O'Swaldkai

Hamburg erhält eine Mehrzweckanlage: den HHLA Terminal O'Swaldkai, der alle Anforderungen des Hafenumschlags erfüllt. Mit RoRo-Rampen (RollOn-RollOff), Schwerlastkränen und Containerbrücken ist der Terminal bestens

ausgestattet.

1976

Gründung von Hamburg Port Consulting

1976 gründet die HHLA die Hamburg Port Consulting (HPC), um unsere Expertise weltweit anderen Häfen zugänglich zu machen. Bis heute unterstützt HPC global Hafenbetriebe mit fundiertem Wissen und innovativen Lösungen.

1975

Beteiligung an Hansaport

Die HHLA erwirbt 49% der Anteile an der Hansaport Hafenbetriebsgesellschaft. Die Anlage für Kohle und Erze bewegt heute bis zu 15 Prozent der gesamten Umschlagmenge im Hamburger Hafen.

1972

Erste Tochterunternehmen der HHLA

Seit 1972 organisiert der CTD Container-Transport-Dienst als erste HHLA-Tochtergesellschaft Hinterlandtransporte und Hafenumfuhren. Mit der Zeit kommen immer mehr Tochterunternehmen hinzu.

1968

Beginn des Containerzeitalters

Mit der Ankunft der ersten Containerschiffe in Hamburg wird unser HHLA Container Terminal Burchardkai zur ersten Spezialanlage für deren Abfertigung. Wir entwickeln und testen innovative Umschlag- und

Transporttechniken, die schnell effizient zum Einsatz kommen.

1966

Die rollende Fracht erreicht den Hamburger Hafen

Wir wandeln eine ehemalige Rollanlage der britischen Armee zur ersten Anlaufstelle für RoRo-Fracht (RollOn-RollOff) im Hamburger Hafen um und setzen damit einen Meilenstein in der Logistik.

1961

Innovative Fruchtlogistik macht Hamburg zum Fruchthafen

Wir errichten den modernsten Bananenschuppen Europas. Mit Elevatoren gelangen die Bananen wettergeschützt in die Lagerhallen. Weitere Innovationen folgen und machen Hamburg zu einem der führenden Fruchthäfen weltweit.

1952

Moderne Gabelstapler revolutionieren die Hafenlogistik

Bis 1952 dominierten Sackkarren die Hafenarbeit. Mit dem Einsatz moderner Gabelstapler für Stückgüter – Schwergutstapler gab es bereits – wird bei der HHLA nun schneller und effizienter gestapelt.

1945

Wiederaufbau von Hafen und Speicherstadt

Im Zweiten Weltkrieg wurden große Teile des Hamburger Hafens und der Speicherstadt zerstört. Die HHLA startet nun ein gigantisches Wiederaufbauprojekt – ein Schlüsselmoment für Hamburgs Hafen!

1935-1939

HFLG übernimmt Kaiverwaltung und wird zur HHLA

Um Defizite der staatlichen Kaiverwaltung mit den Überschüssen der HFLG, unserer Vorgängerin Hamburger Freihafen-Lagerhaus-Gesellschaft (HFLG), auszugleichen, fusionierten beide Einrichtungen. 1939 entsteht daraus die

„Hamburger Hafen- und Lagerhaus-Aktiengesellschaft“ – die heutige HHLA.

07.03.1885

Gründung der HFLG und Bau der Speicherstadt

Mit der Gründung der Hamburger Freihafen-Lagerhaus-Gesellschaft (HFLG), unserer Vorgängerin, beginnt der Bau der Speicherstadt. Bis heute handelt es sich um den größten Lagerhauskomplex der Welt.

1866

Gründung der Kaiverwaltung und Eröffnung des Sandtorkais

Mit der Eröffnung des Sandtorkais beginnt in Hamburg der moderne Umschlag direkt an der Kaikante. Für den Hafenbetrieb wird die Kaiverwaltung gegründet, mit der wir als HHLA später fusionieren.