In recent years, things have become a lot easier for rail transport in cross-border traffic, sums up Josef Doppelbauer, Executive Director of the European Union Agency for Railways (ERA). But he also sees shortcomings. Some freight trains are stuck in border areas for far too long because of national safety regulations, and there are capacity bottlenecks in the infrastructure of many countries. Read the whole interview in HHLA Talk.

First and foremost, we would like to speak with you about rail transportation in cross-border traffic. What has this kind of freight transport simplified for European RUs in the past few years?

One thing has clearly improved: the introduction of EU-wide vehicle approvals for freight wagons, which have been issued by the European Union Agency for Railways since June 2019, will save RUs considerable time and costs in bringing rolling stock to market.

Even so, there are still different technical standards in many countries, as well as other requirements that make cross-border transport solutions more difficult. What is the main obstacle in your opinion?

Our own study shows that rail transport of goods can achieve significant time savings when technical and operational processes in cross-border transport are harmonised. Since 2016, ERA has reduced the number of technical regulations for vehicles from 14,000 to fewer than 1,000 — however, the remaining national regulations can be the cause of critical loss of time at the border, as we found out in our analysis of the freight route from Brenner (Italy) to Steinach in the region of Tyrol (Austria). Freight trains are stopped at the border there for nearly an hour due to national security regulations — and it's exactly such regulations that make it more desirable to transport freight by road, where these regulations simply don't exist. We need national decision makers to have a European mindset. Today, European connections must be offered to European citizens. The time of thinking at a national railway scale must come to an end.

With what means do you intend to change that?

At the ERA, we want to further reduce national safety regulations with the help of national authorities. We also want to further promote the technical harmonisation of the European railway sector with improved technical specifications (TSIs). The framework will have backwards compatibility to protect existing investments and comes in a package to support future technologies such as the new FRMCS radio system, automated driving, cyber security and automatic coupling. This is the technical contribution to the Europeanisation of the railway system. However, this must be accompanied by the strong political will to invest in the rail system and by a European mindset when it comes to planning and coordinating cross-border traffic.

Let's look for example at a peculiarity that is currently very much in focus: the differences in setting energy prices. In Germany, RUs can buy their own energy. In countries like Slovakia or Hungary, energy volumes are purchased centrally via a state institution for all RUs. How is a European company meant to calculate its prices and ensure plannability with these kinds of conditions?

In times of crisis, the task of regulating prices in the energy sector often falls on the shoulders of the sovereign states, as we're seeing right now. In this regard we also need European coordination in price policies so that all competitors in all member states are able to work under uniform, fair conditions.

Is it possible to establish an international electricity price or price cap?

It is certainly possible at the European level, but this would require a consensus from the EU member states.

There are bottlenecks in many countries' infrastructure. How could the overall conditions for freight transport be improved?

We need more resolve in implementing European regulations. Especially when it comes to freight corridors, we are regularly seeing that the infrastructure of individual member states is operating on time and in conformity with regulations, while nothing has happened yet in certain parts of the process in other member states — which means the entire logic of the cross-border corridor is broken. You have to ensure that the individual cogs of the whole system mesh well and thus also make cross-border transport economically attractive. It's often local politicians who have a real interest in cross-border freight transport; unfortunately, their enthusiasm is often curbed by national mechanisms.

Would it be possible to eliminate the discrimination against freight traffic compared to passenger traffic?

It is possible; however, the trend of the past few years shows otherwise – because you would need redundancies in the network. In Germany, for instance, these redundancies have been dismantled over the years to reduce costs in the short term. So, these days you rarely have any alternatives, even in the arteries of the system. It will take decades to reverse this development, and in many cases it will be impossible because the corresponding plots of land and rights were also sold.

We must now focus on making the best of the currently available routes and increasing capacities. Modern, integrated, digital train control makes it possible to plan and coordinate down to the minute, and this might offer the possibility of at least partially eliminating the general discrimination against freight traffic vis-à-vis passenger traffic.

How does the EU's Green Deal support the environmentally advantageous rail transport?

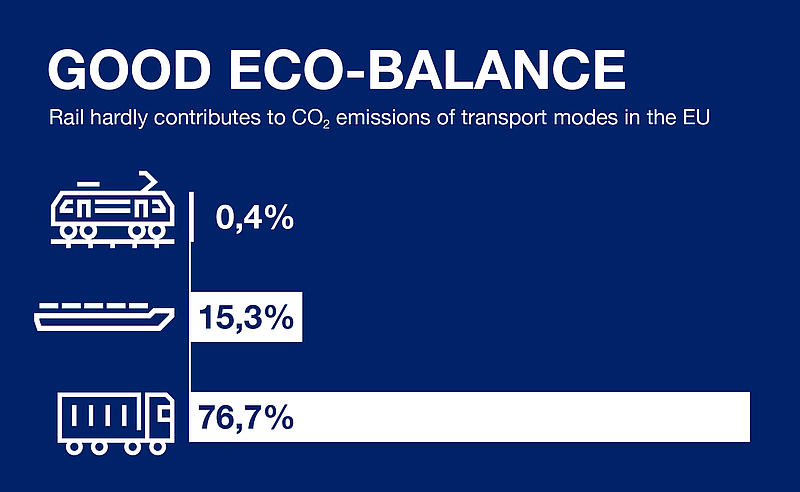

The EU Green Deal formulates ambitious goals at the highest political level to make the European economy climate neutral by 2050 – with concrete goals for European traffic, where the emission level is to be reduced by 90% by 2050. The plan is to achieve this, at least in part, by doubling the share of freight transport by rail.

In 2023, the TEN-T Regulation will be modified to put an explicit focus on the nine European freight corridors. For example, short waiting times for freight traffic are to be established on the corridors. There are also discussions regarding a system-wide standard to bring trucks onto freight trains.

This is when the keyword “digital coupling” comes into play. To introduce it, the costs per wagon are estimated at € 30,000 – 35,000. Are there potentially more efficient innovations that could be made in rail transport for less money?

The expected benefit of digital coupling (DAC) is that rail freight transport leaves behind the technical standard of the 19th century and, like the rest of the transport system, arrives in the 21st century. For the digitalisation of the railway, and thus a significantly improved service for customers, DAC is unavoidable. As a matter of fact, bringing an efficient, standardised technical solution to market is unavoidable – only then will the investments pay off. We are in constant communication with our partners from “Europe's Rail Joint Undertaking” to make this happen.

Should a digital coupling be introduced throughout Europe? If so, who would pay for the conversion?

Yes, the digital coupling needs to be introduced at the European level, and one of the ways to fund this will be through European co-financing.