Your brand new reports contain some surprises. Which figures were the most surprising for you?

The biggest surprise for most audiences was the resilience of trade and other aspects of international business activity during the Covid-19 pandemic. Many business people, as well as members of the general public, are familiar with supply chain disruptions caused by the pandemic, but far fewer are aware that trade only declined briefly and then grew substantially during this period.

While there were shortages, far more goods were delivered across national borders during most of the pandemic period than before it. From the Trade Growth Atlas, one of the results your readers may find surprising is that trade patterns actually shifted much more dramatically between 2000 and 2010 – back when China’s share of global trade was growing rapidly – than they have since then.

Steven Altman is not only Senior Research Scholar at the Stern School of Business der New York University but also Director of the DHL Initiative on Globalization. Together with Caroline Bastian he authored the DHL Global Connectedness Index 2022, which looks at developments in the size and geography of international trade, capital, information, and people flows, and the DHL Trade Growth Atlas 2022, which looks more deeply at trends specifically in international trade and where companies can find the most promising growth opportunities.

Then, another surprise from both reports is that trade took place, on average, over longer distances in both 2020 and 2021. Many expected that the pandemic would cause a shift toward more trade happening over shorter distances due to pandemic-related disruptions and business efforts to promote regional sourcing. But instead, trade happened, on average, over longer distances due to the relatively greater resilience of production in Asia during the first two years of the Covid-19 pandemic. That led to more long-distance trade between Asia and other regions.

Is this a change that will stay?

It will be very interesting to see if trade starts to take place over shorter distances moving forward, as many companies and governments promote nearshoring. In our DHL Global Connectedness Index report, we consider the arguments both for and against the possibility of a shift toward more regionalized trade patterns. Finally, another surprise in the DHL Global Connectedness Index report was that even as we found substantial evidence of U.S.-China decoupling in trade and other types of flows, we did not find similar patterns for countries that are geopolitically aligned with the U.S. and China. At least through 2022, we concluded that U.S.-China decoupling has not led to a wider fracturing of the world economy into rival blocs.

In which regions of the world and in which countries was there the strongest growth in global trade?

Our Trade Growth Atlas focuses on comparing the last 5-year period as of the time we produced that publication (growth from 2016 to 2021) to the growth forecasted by the IMF over the next five-year period (2021 to 2026). From 2016 to 2021, the fastest exports volume growth was in China, closely followed by the ASEAN region (Association of Southeast Asian Nations). The forecast at the time of that publication (mid-2022) for the period from 2021 to 2026 showed ASEAN moving up to first place with the fastest exports growth, with South & Central Asia moving up to second place. Generally speaking, Asia is likely to continue leading the world in exports growth, but within Asia, we are seeing shifts to the south and west.

Can strong economic growth occur without global connectivity?

A balanced answer to this question must take two considerations into account. First, global connectedness makes a clear positive contribution to economic growth. So, developments that strengthen connectivity promote growth, while developments that reduce connectivity slow (and in some cases even reverse) growth. That said, though, a second perspective is also important. Most economic activity is domestic, not international. So, economic outcomes in a given country are usually shaped more by domestic rather than international developments. Therefore,we should not exaggerate the role of global connectivity in growth – or in other economic outcomes such as inequality.

More maritime trade, less poverty?

An important study on the impact of global trade shows: more protectionism hits poorest harder; fewer restrictions help everyone.

Learn more

In your outlook, you predict the fastest changes in trade growth for previously less connected countries such as Uganda, DR Congo, Senegal or Niger. Do these economies have the most ground to make up, or are there specific reasons in each case, for example raw materials in demand in these countries?

Without commenting on specific countries, both of these factors are often at play in the countries with the fastest trade growth. The fastest trade growth is often in countries that are starting off at lower levels of trade integration, and it is often where natural resource exports are expected to grow swiftly. While major accelerations in a country’s trade growth can result from shifts in either demand or supply, the fastest growth often occurs when new sources of supply come on line, such as when a country starts exporting a commodity that it previously did not export or when a country brings a major new source of production on line and starts exporting the output.

Germany, too, has only placed itself pretty much in the middle in the Speed Ranking with 87th place, and the outlook looks even worse. Has this successful economy achieved so much in the last decade that further growth hardly seems possible?

I would not look at it in this way. A large advanced economy such as Germany cannot be expected to grow its trade as fast as the smaller emerging economies that tend to achieve the fastest growth (“speed” ranking). Instead, in the case of Germany, I would focus on the country’s third place “scale” ranking, which highlights how, even though Germany’s trade growth is relatively slower, the total amount of trade growth that is likely to take place in Germany is among the world’s largest.

Based on the IMF’s April 2022 forecast (the most recent forecast at the time of our Trade Growth Atlas publication), Germany was expected to achieve roughly half as much absolute trade growth as top-ranked China and almost as much as second-ranked United States.

The eternal power of the global differential

Christoph Schwennicke has been an influential journalist for more than 25 years, among others for “Süddeutsche Zeitung”, “Spiegel” and as editor-in-chief of the political magazine “Cicero”. He also has his very own opinion on the subject of globalisation.

You break down world trade according to the Harmonised Commodity Description and Coding System (HS). Which traded goods systematized in this way have lost a lot of ground in the last five years, and which have gained the most?

In our Trade Growth Atlas, we focused on changes in the mix of products traded over the longer time period from 2000 to 2020. The largest absolute amount of trade growth over that period was in Electrical Equipment and Machinery, followed by Industrial Machinery, and Mineral Fuels, Oils, and Waxes. The fastest growth was in Ores, Slag, and Ash (a category that includes raw metals such as iron and copper), followed by Pharmaceutical Products, and Other Made-up Textile Articles. The growth of trade in Other Made-up Textile Articles (which includes face masks) was due to the Covid-19 pandemic, which caused a surge of trade in such products in 2020.

In your opinion, what contribution does the maritime industry make to world trade? Can its expansion accelerate globalisation - or is it only dependent on economic growth?

The maritime industry plays a crucial role in globalization, since the large majority of world trade (by volume) is transported by sea. Historically, improvements in the efficiency and reliability of maritime shipping have contributed powerfully to the growth of global trade, and I expect that this relationship should continue to hold. The maritime industry can also play an especially important role in reducing the environmental impact of international trade due to both the relative efficiency of maritime transportation as well as efforts underway to reduce maritime emissions.

Have the many global crises, catastrophes and wars recently loosened the close ties of the world economy?

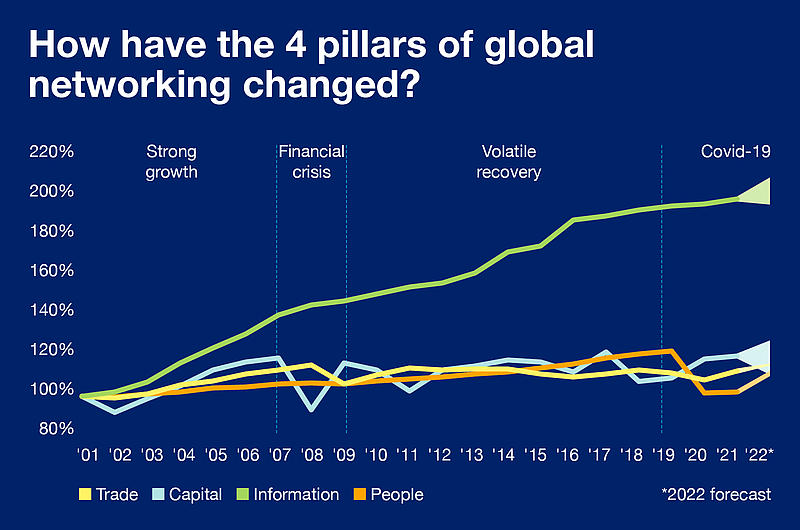

Contrary to predictions, globalization has proven surprisingly resilient through recent shocks. This was a major theme of our 2022 DHL Global Connectedness Index report. Trade, capital, and information flows have already rebounded to above pre-pandemic levels. As of mid-2022, the global volume of international trade in goods was 10% above its pre-pandemic level, before it weakened somewhat in late 2023. And there is now more than twice as much data crossing national borders as there was in 2019.

The only aspect of globalization that remains below pre-pandemic levels is international travel, but this is clearly recovering. The latest UN forecast predicts that international travel will be just 5-20% below pre-pandemic levels worldwide in 2023, and some regions, including Europe, could be fully back to pre-pandemic levels of travel this year.

There is a lot of tension and even sanctions between the US and China. Will global growth be affected by this in the coming years?

We do find a clear pattern of U.S.-China decoupling, however, it is still a partial decoupling. More goods still flow from China to the U.S. than between any other pair of countries – but it is a clear decoupling trend between the world’s two largest economies. We do not find, however, a general parallel pattern of “fragmentation” or “fracturing” splitting allied countries into rival blocs.

For example, through 2023, U.S. allies (as classified by Capital Economics) slightly increased the share of their imports coming from China, while the U.S. decreased the share of its imports coming from China. There is not, at least yet, a major fracturing of global flows along geopolitical lines. However, if we ultimately do see a major split develop between rival blocs moving forward, that would probably have a large negative effect on economic growth. It is an important risk that must be considered.

If you want to dive deeper into the figures, you can download the two studies mentioned here for free:

DHL Global Connectedness Index

Published 2.6.2023