66 faithful years of service: Time for the HHLA IV to go into its well-earned retirement? No, the floating crane built in 1956 by Demag and put into operation in 1957 is far from hoisting its last load. Its services are in high demand in the Port of Hamburg – as are those of its sister crane, the HHLA III, which is 16 years its senior.

That’s why the grey giant with its 55-metre jib, which is able to lift over 200 tonnes nearly 32 metres into the air, is now being retrofitted for the future. For a sustainable future, that is! Retrofitting does not require the construction of a new crane, which would result in very high requirements in terms of energy and materials for such a large piece of equipment.

Retrofitting avoids complex new construction

“This is the first major retrofit of the HHLA IV in seven decades of service,” says Stephan Fröhlich, Head of Floating Cranes at Hamburger Hafen und Logistik AG. The project is based on the original construction and schematics from the 1950s. The retrofit should ensure the machine can continue to function for at least a further 15 years. By then, the crane will be celebrating its 80th birthday. This is the face of sustainability at HHLA. So, what form does this kind of major retrofit take?

September 2023, the sun is shining over the Port of Hamburg. Even from a distance, it is possible to make out that extensive work is being undertaken on this specialist crane: The superstructure is surrounded by scaffolding and wrapped in construction sheeting. The jib was removed in summer 2023 by HHLA III, working alongside mobile cranes. The mobile structure has now been deposited on the quayside in five segments.

The lifting link is currently covered with a corrugated roof, while the historic steel structure is undergoing thorough renovation in the mobile hall: it’s time to remove the signs of wear and the old paint, carry out the necessary repairs and apply the new anti-corrosive coatings. The gigantic bearings are also being repaired at the same time. Covered by sheeting, the relevant work is being completed on the tower of the self-propelled pontoon.

Good maintenance by the HHLA team pays off

Entering the tent, the jib appears even more gargantuan in the fading light than it does up on the superstructure. Head of Floating Cranes, Mr Fröhlich, is delighted that the number of damaged connectors and sheets is so small – it shows that the good maintenance of the floating cranes provided by the HHLA team pays off. The historic rivets from the 1950s are not replaced with new rivets if they are damaged but with screws. These screws are as thick as a finger and can bear weights of many tonnes thanks to their safety and efficiency.

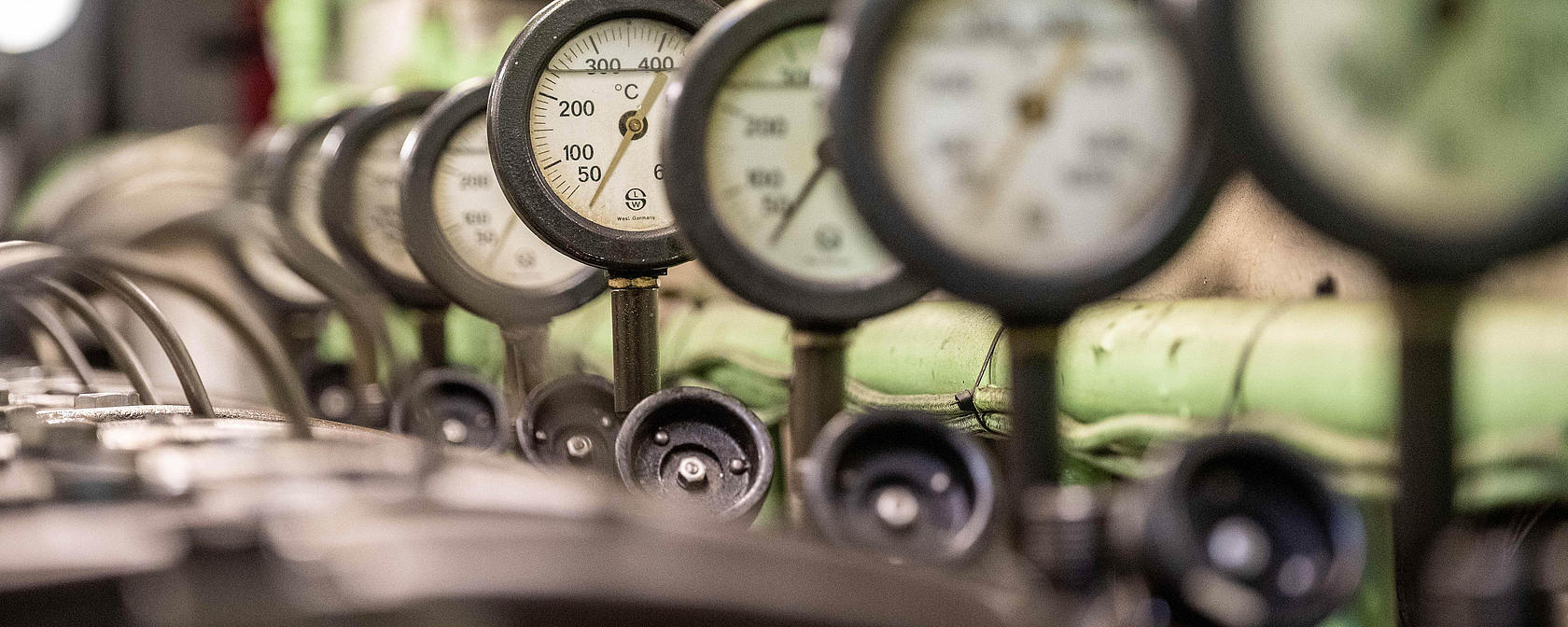

Machinist Heinrich Proes is currently up to his elbows in a piece of mechanical engineering history. The inland shipping specialist has been part of the Floating Cranes team of 19 years. Currently, he is removing the nearly 70-year-old roller bearings, which enable the gigantic jib to move on the crane superstructure. Of course, the ravages of time are clear to see. But Mr Proes is happy with how well the historic equipment has held up despite their regular use over such a long period of time.

After all, one of the two cranes is in use at least once a day. Replacing the bearings on the historic hoist also won’t be a problem, Mr Proes says. This is because standardised components were already being used in 1957 and these are still around. There are also suitable replacements for the enormous bearings from FAG Kugelfischer.

Construction continues to be perfectly suited to specific tasks

But why is HHLA going to the trouble of retrofitting the cranes? This is primarily because the mid-20th century construction continues to be perfectly suited to specific tasks in the port. Since the 1960s, most goods have of course been handled by the container gantry cranes. But there are still occasionally heavy loads and oversize dimensions that need handling.

These include things like ship propellers, that can weigh more than 100 tonnes, and components for offshore wind farms. This is where HHLA’s two floating cranes come in. They can lift very heavy loads very flexibly, transport them autonomously and load them onto enormous ships. For the heaviest loads, the cranes can even work in tandem.

“The fact that our cranes can turn 360 degrees is almost unique in heavy goods handling in ports today,” Heinrich Proes says of the cranes’ special abilities.

“The fact that our cranes can turn 360 degrees is almost unique in heavy goods handling in ports today.”

This is made possible by their traditional construction: A cone-shaped steel-frame tower is securely attached to the pontoon. The continuously rotating superstructure is slid over this like a hood. Towards the top of it are the bearings of the jib construction with the lower arms (hitch lifting arms) and upper arms (upper links). The tip of the jib completes the geometry at the front, with the counterbalance at the back.

Together, the lower rotating assembly and tip of the load-bearing construction bear the vertical and horizontal forces. A whole battery of slip rings at the heart of the superstructure transfer the electrical energy and control signals between the superstructure and the vessel.

The team of nine under Stephan Fröhlich takes great care to ensure their equipment is properly maintained and that all deadlines are observed. New steel cables are installed every ten years. The crane goes into the dry dock every five years to clean the hull of the pontoon and repaint it. The crane components are lubricated every six months. Machinist Proes climbs up to the very top with the lubrication gun. In addition to the maintenance schedule, the equipment is also reclassified regularly. The older HHLA IV has already received its reclassification in December 2022. The crew sees that as a good omen for the successful completion of the work currently under way for HHLA III.