The audio part is only in German available, below you will find the English transcript of the entire interview.

I have two guests here today, who could start by introducing themselves. Good morning.

Ulrich Spindel: Good morning. I’ll start then. My name is Ulrich Spindel. When we were building the Altenwerder Terminal I was responsible for the IT. And for everything related to it. So for the software, the hardware, the infrastructure, selection, market research, DIY... Right through to the start of operations and afterwards too.

Martin Schubring: My name is Martin Schubring. I joined HHLA in 1999 and from day one was responsible for the procurement of container gantry cranes. That’s why I was then assigned to the Altenwerder project for the procurement and commissioning of the handling equipment, which I was responsible for.

Question: To start with today we looked at a few old photos. Some of them looked like some kind of enormous roadworks. When you think back: what is the first thing that comes to mind?

Ulrich Spindel: Lots of sand. The first time I was in Altenwerder it was a spoil area. You could see sand and water and not much else.

Martin Schubring: Yes, that’s how I remember it too. There was a small site office from the Hamburg Port Authority and loads of pipes, that pumped out sand and water continuously. That brought the ground level up to the right height, and then it was huge desert.

In fact, they only started levelling the ground and building the quay wall shortly before they set up the construction site. Martin, can you tell us anything about the preparation work?

Martin Schubring: Yes, the HPA carried out the preparation work, because in Hamburg it is responsible for securing the banks, so in this case the quay wall, and for setting up what is known as the formation. That is the foundation area, that has to be brought up to the desired elevation. So the HPA pumped in vast quantities of sand, which would certainly have required some serious material management in the Port of Hamburg, and then started to design and build the quay wall. It might sound a bit surprising, but it was actually a land-based site. That means the HPA built the quay wall into the existing embankment. And it was only when it was finished that they dug away the material in the water on the seaward side.

Another part of the preparation was all the paperwork you did in the Speicherstadt historical warehouse district. You were busy for a whole year drafting various different handling concepts and presenting them to the Executive Board. Which of you was involved in this part of the preparation phase?

Martin Schubring: Well, I had a lot to do with the preparation phase, because I was there from day one. It started with setting up a small project team. To begin with there were just 5 to 7 people who sat in three offices in Block T in the Speicherstadt and spent their time thinking. How could we build a container terminal on a greenfield site, or rather on this strip of sand? So we looked at all the different types of handling systems that there were in the world – some of them were tried and tested, others hadn’t been proven yet – and compared them. We boiled all the options down to five, and then our team, which was gradually getting bigger, chose three handling systems out of these five. They were examined in detail, analysed from a financial perspective, and then presented to the Executive Board for a decision.

It was a total greenfield project; something like this had never been done before. You could say you built it from the drawing board. But talking about automation: of course that means the IT must have had a very special role to play there. Ulli, maybe you could tell us a bit about the role of IT? You couldn’t just buy it off the shelf back in those days.

Ulrich Spindel: Yes, but we didn’t know that at the time. IT really got involved when the decision had been taken to go for a system with AGVs (autonomous container transporters) and twin-trolley gantry cranes. We started with research, and looked at 33 providers operating around the world to see if they were capable of supporting such a system. The result was that none of the 33 met the requirements. There were two main reasons for that. One was this automatic concept, which called for a high level of automation not supported by the standard systems. And then there was the Hamburg environment. By Hamburg environment I mean the data connections that existed in the Port of Hamburg; to the centralised systems, to the freight forwarders, the ship managers and so on. Of course none of them were included. So all this led to the decision by HHLA to build its own system. At its core is an automated control system that links the different components together: the vehicles for horizontal transport, container gantry cranes, the yard and the tractor units in the hinterland.

So that is what is known as the Terminal Operating System or TOS.

Ulrich Spindel: Exactly, the name says it all. The system supports operations at the terminal.

And you used a programming language that was pretty new at the time, didn’t you?

Ulrich Spindel: We started with two preliminary studies in 1999. One was a preliminary architecture study that laid the groundwork and led to several decisions being taken. One was that the programming should be what is known as “object-oriented”, and that we should use the Java programming language. This was particularly interesting because it was one of the few that could run on different types of hardware. We selected a wide range of tools and frameworks and a database too. That was the second preliminary study, the database review, where we looked at two different databases, which also worked on the basis of different systems. By the way, that is actually an example of a bad decision we took. We had decided in favour of an object-oriented database, which looked good in the tests and actually should have been a good fit with our structure. But after about a year and a half it turned out that it was not well suited to operating phases. We had to make a U-turn because we had run into a dead-end. So we changed tack and carried on down a different path.

Did that also happen with the technical equipment? You had to buy new operating machinery, like the AGV. Could you just explain the concept to us again, Martin? AGV like that were not in service anywhere at the time, were they?

Martin Schubring: That’s not quite right. Rotterdam introduced an AGV system for its ECT terminal at the beginning of the nineties, so around eight years before us. And they really learnt the hard way. We went there several times of course to have a look. And this prototype AGV system was the precursor of the system that we built along with our partner Gottwald. The vehicles we built back then are now the global standard – apart from the drive train, of course, because they are now battery-powered. Gottwald and its successor still distribute them worldwide in the same form today and have now built hundreds of them. Other manufacturers are also giving it a try. From the conceptual point of view, the vehicles are identical to the ones we developed back then.

Yes, but the concept for how the vehicles should move, that was completely new. I remember in Rotterdam they always drove on a track, so they had to queue up. But what you developed, which really was an autonomous vehicle that could move around relatively freely in a given space; we were the first to have those, weren’t we?

Martin Schubring: That’s true. Working with our supplier we created a system in which the AGV could basically drive around on their own. Well, they could follow the transponders that had been embedded in the ground, moving along from one to the next. There was a network of these all across the terminal, and in theory we could have programmed any route and the AGV would have been able to follow it. In practical terms it does come down to fixed pathways in the end, but there are very, very many of these and they are very well planned, so we avoid vehicles having to queue up behind each other. That is highly flexible and autonomous.

So this was another job for the programmer, wasn’t it? I once heard a completely mind-boggling figure for the number of lines of code that had to be written for it. That was quite a task; you really had to invent something new then, didn’t you?

Ulrich Spindel: It had to be built completely from scratch, which is why we started with the preliminary study for the architecture. There were 1.8 million lines of code in total for the control system. But the software we bought on top – the whole terminal operating system doesn’t just consist of this one component, there are others too – has about another million lines of code. So the system did get relatively big, but it has to be said: it’s still running to this day! And it’s still extremely productive. Altenwerder is still a highly productive terminal, the most productive one at HHLA. And it has been upgraded over the years, of course it has. But the groundwork we did back then has really stood the test of time.

Something that is hard for us to imagine nowadays is the capacity of the hardware. So if you were to compare it with a modern smartphone – what were you working with back then?

Ulrich Spindel: Basically you can say that the performance of electronic devices, the computing power, doubles roughly every two years. So you can work backwards, also if you look at the network capacities, for example. We had a three-tier network architecture then, and the backbone consisted of a 1 gigabit connection. Then there were the various lines attached to it with 10 megabits. Today’s backbones have a capacity of 100 gigabits. So it is a completely different world.

Talking about different worlds. Maybe we can take a quick look back at how the terminal was built. Where did they put you up there, at the beginning? Were there office containers, or did you always have to drive out to Altenwerder from the Speicherstadt? Tell us what it was like.

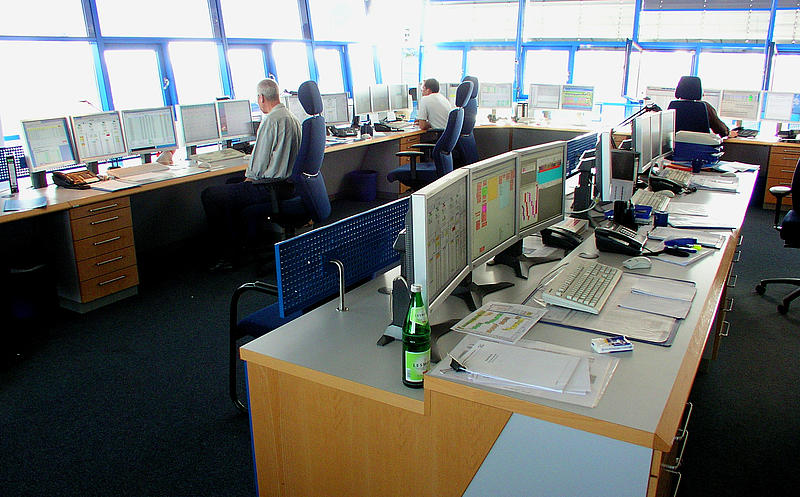

Martin Schubring: Well, we planned the terminal in the Speicherstadt. We moved once within the Speicherstadt and at the end of the planning phase we had an open-plan office, a whole floor in fact, where we all sat together, which was very effective. The first ones to move out to Altenwerder were our construction engineers, obviously, because they created the foundations for everything else we put on top. The workshop building went up pretty quickly. That provided a certain amount of accommodation, even if was a bit spartan. My group, so I and my colleagues from handling systems, moved in there and used that as a base for the further work on the terminal and to manage things on site. The first pieces of handling equipment were delivered or installed around that time too. That meant we had to be on site; we all sat on top of each other and the facilities were not so great. But we were an established team, so nobody minded being perched together like that for a while. We were right at the heart of the action. It was a very effective time, and really enjoyable too, I have to say.

Ulrich Spindel: Of course the people in charge of the hardware, the infrastructure and the network, a lot of them were on site, logically. They also worked in temporary rooms like those Martin just described. But the majority were in the Speicherstadt. That was also a decision, that the main hardware should be in the HHLA data centre – which is in the Speicherstadt – and only the computers needed locally should be on site.

Martin Schubring: There’s a story I can tell about that. We were sitting here in the Speicherstadt and at some point a company was established called CTA GmbH, whose address was Sandtorkai. So one day the doorbell rings and a lorry driver comes in and says he has to deliver a transformer to this address in the Speicherstadt. We looked out of the window and saw a flat-bed truck with one of those huge 110 KV transformers on it, bigger than a tiny house, and the poor driver was standing there with his transformer in the Speicherstadt and wanted to offload it. So we gave him the right address and he had to try to manoeuvre out of the free port and get the transformer where it was supposed to go in Altenwerder.

Ulrich Spindel: Talking about the free port, there’s another important thing. It was certainly a big deal for the IT, because Burchardkai and Tollerort, the other two HHLA terminals, were inside the free port, and Altenwerder was on the outside. Now the free port doesn’t exist anymore, but at the time it was very important. We needed a customs system, and we knew nothing about that. Normally we had nothing to do with customs duty, and it was another major step to build the whole IT system for that.

On the subject of communication: I think around 1999 there were no mobile phones, or not very many at any rate.

Martin Schubring: They started to get popular around then. And I can well remember the discussion about whether only the project manager should get a mobile phone, or other people as well. The decision was finally taken to give more people a mobile phone, so that they could be reached on the building site. And then we got one of those good old Nokia phones. It worked very well for the next ten years.

One of the biggest challenges was the time pressure you were up against. Maybe you can just give us an idea of how long it took from the planning stage until the first ship actually docked there. I think people today would find it hard to imagine the timeframe you had back then. I mean how fast everything went in those days.

Martin Schubring: That’s correct. The decision that HHLA was allowed to build in Altenwerder was taken in late 1997. The planning team was set up in the first half of 1998 and got right down to work. In mid-1999 the decision was taken for the handling system that was finally implemented. And in parallel we started writing the tenders for IT, construction and handling equipment. In 2000 the handling equipment arrived; the individual components were wired up and connected to the IT. The commissioning phase for the terminal started in 2001 and in March 2002 we began commercial operations. So it took three years and a bit from the start until we handled the first commercial ship.

Wow! You couldn’t do that anymore today. What were the main factors that helped you?

Martin Schubring: Well, we had two very dynamic people behind us; the Executive Board member Dr Behn and the overall project manager Dr Koch. These two people worked in the background and they were able to convince the politicians, and above all the various authorities that had to approve the project. So much so, that some of the officials at the authorities and the insurance companies still say: we helped to build that terminal! We were able to integrate the people issuing the permits into the team. That was a real achievement and it speeded everything up. They didn’t just apply the letter of the law, but thought about what they were doing and interpreted the rules accordingly. Especially because many of the rules for an automated system didn’t even exist. In other words, they really just thought about it and worked it out, always in accordance with their official responsibilities of course, and with the law. It was a really constructive working relationship, so in fact we didn’t have any obstacles to overcome in this area. And I should add: to this day there has not been a single deadly or really serious accident in Altenwerder.

Ulrich Spindel: And we were fully focused. There was this project, which ran for three or four years, and the project members weren’t “disturbed” by other projects or other operational factors. So that was certainly one reason why we were able to build a sustainable system in such a short time.

Were there any challenges with suppliers, because some of them you didn’t know beforehand? Like new technology from Sweden, or the big Chinese firm ZPMC, which makes container gantry cranes and was just starting out on the European market back then.

Martin Schubring: Yes, that’s true. But they were very interested in establishing a foothold in Europe and so we had an excellent working relationship. And that certainly applies to our European partners from Germany, Austria or Sweden. I think they all did good business with us and together we built a very good terminal. The biggest risk was that one of major components, like the gantry cranes, the storage system or the IT, came much later than the rest. Then we would have had the depreciation for everything else and still not been able to start operations at the terminal. In fact, we finished about four months later than planned, or than our ideal date, but at least everything was all finished at the same time.

So if you hadn’t made the deadline, then a lot of equipment would just have been standing around, and you would already have invested in the software, and so on. And then the financing might not have worked out so well?

Martin Schubring: The start-up costs were certainly very high, there’s no getting around it. And of course they would have been considerably higher if we hadn’t managed to start commercial operations when we did.

Ulrich Spindel: And operations started at a time when the market was just perfect for CTA. That was the start of a period of very strong growth in container traffic, with double-digit annual increases. Altenwerder was a perfect fit in this situation and was able to soak up those volumes.

Did you encounter any resistance from the city council, in fact, back in 1999? Or did everyone say: Yes, it’s great that we are starting to expand the port. That can only be good for Hamburg.

Martin Schubring: Well, we didn’t get any resistance. I’m not sure exactly how it was for the Executive Board. But as we in the project team had a very direct line to the Executive Board back then, I think we would have noticed. So I think there was very little resistance from the city of Hamburg. It was 30 years earlier that the village of Altenwerder had been demolished to make way for an oil terminal, which in fact was never built.

And then the first container gantry crane arrived. Martin, do you remember that moment too?

Martin Schubring: Yes, the gantry cranes were built in Shanghai and delivered almost fully assembled by ship. They couldn’t be fully assembled, because they had to fit underneath the Köhlbrandt bridge. And when the first two gantry cranes arrived on the transport ship there was suddenly a big thunderstorm. So the arrival of the first CTA container gantry cranes was very dramatic, accompanied by thunder and lightning. My colleague Antonio Schmitt, who was responsible for the gantry cranes, and I gave ourselves a treat and watched the entire unloading process. It carried on into the night, and eventually, as you do, you get a bit tired. So we sat down on a pile of timber and watched the Chinese guys working. Then all of a sudden, the ship’s captain came up to us with six bottles of Tsingtao beer in his hand from his duty-free allowance. He sat down next to us and the three of us all drank a nice bottle of beer each. I probably shouldn’t say that at HHLA, but at the time it wasn’t HHLA yet.

That’s a good story! There are a few other good ones too, that you told me earlier. They weren’t about beer, though, but coffee. How did it go with the coffee machine?

Martin Schubring: Oh yes, when the operations building was finished and the control centre people started taking over after operations had begun, there was a pantry with a coffee machine at the back of the control centre. And unfortunately someone had made the mistake of running this coffee machine on the same wiring circuit as the monitoring panel for the automated handling operations. And what sometimes happens with a coffee machine happened and it blew a fuse. Which brought the whole terminal to a standstill, because of course the monitoring panel had no power either. So the coffee machine caused the entire terminal to crash.

People always like to hear about that sort of thing: cock-ups and blunders.

Martin Schubring: Yes, that reminds me of another strange story. As I said earlier, the AGV navigate around the site using transponders embedded in the ground. The transponders are inserted by cutting a hole in the asphalt, putting the transponder in it and then sealing the hole with a special kind of mastic. But that can only be done when the ground is dry. We had a small building site and there were still about 150 transponders to bury. The holes were drilled, the transponders inserted, and then it started to pour with rain. So the mastic machine couldn’t go over them. The next day the AGV stopped working and we didn’t know the reason why. But there was a simple explanation: crows had pulled the freshly embedded transponders out of the holes and dropped them across the asphalt. Some of the transponders survived the fall, so now there were AGV driving along a route, going from transponder 17 to number 18, number 19, and then suddenly coming across transponder number 245, which cannot be, so they came to a standstill. It took us about two days to find out what had happened. And then someone discovered the transponders.

Yes, that’s a good story. But finally the terminal was opened. And then every trucker who was told to pick up a container started coming to the CTA. I think they were quite surprised to start with. This kind of system didn’t exist at all in Hamburg at the time.

Ulrich Spindel: Yes, though of course we tested it all beforehand. To get the dimensions right, for instance, and the distance between the truck loading bays. At the storage blocks it was vital that a lorry could reverse in. Which is not easy, especially as there were also trucks with trailers, so 60 feet long altogether.

Martin Schubring: They were quite surprised, especially because they had to park backwards, like Ulrich said. But we were also surprised that many of them quite liked it. Finally something to do, proper driving, not just cruising down the motorway, but something requiring a bit of skill. So in the end it all worked out fine.

The container rail terminal in Altenwerder is the biggest of its kind in Europe today. How small was the station in the hinterland when you started?

Martin Schubring: We didn’t start off that small. From the outset we planned a rail terminal with what is known as a full train length of 700 metres and six tracks. In the meantime, about eight years ago, we added another three tracks to the terminal. We moved the tracks closer together and so now there are nine of them. Because fortunately, rail traffic has continued to grow, which is a real boon for Hamburg. CTA is now the rail terminal with the highest throughput in Europe.

So in fact everything worked surprisingly well, and many of the components are still in service to this day, with the latest updates, of course. Now when it came to the official arrival of the first ship, did you look at each other and think, isn’t it amazing that everything has gone so well?

Ulrich Spindel: Of course that is the greatest reward for our work, the fact that the terminal became such a productive facility in such a short time. There were a few mishaps on the way, and some tricky moments during the initial operational phase. It was only at the end of March 2002 that we had access to the whole system for testing, for example. So from then until the operating launch in June we only had about three months to test the entire system. Which is not very long! But since then the CTA has been a success story.

That’s something to be proud of, isn’t it?

Martin Schubring: The team was certainly proud, and quite rightly so. Surprised? No, to be honest, because we had spent a year and half working to these dates, with intensive testing every day and successive commissioning. So we knew it worked.

Which sub-project, which commissioning was the most difficult? Were there any pieces of equipment that didn’t do what you wanted them to?

Martin Schubring: I can’t think of anything now, actually. Of course every system had a few teething troubles to start with, because it was all new, but looking back, I can’t say that we had real problems with any of the handling equipment. Like Ulrich said, there were a few teething troubles, but with the help of our excellent partners on the supplier side we were able to get rid of them methodically, one by one. Our suppliers were also really ambitious and wanted to get everything perfect, not just good enough. I think that was also one of our great strengths, that we were all 100 percent committed and gave everything we had.

Ulrich Spindel: There was a certain scepticism about the question: “Is the system ultimately how it should be?” Does it do what it should? Is it robust enough, does it deliver the performance? With the IT we advanced into new areas that we had little experience with. So to that extent it was a risk. Just like with other decisions that involved breaking new ground: a lot more could have gone wrong than what did actually go wrong. For the IT the biggest challenge was the system as a whole, I mean the interplay between the components, especially the transfer from one automated system to another, so from the yard crane system to the AGV system, for example. You can imagine how accurate that has to be if there are no human beings involved. The crane has to be in the right place at the right time, and the right AGV has to be in the right place. If the AGV isn’t there, the crane puts the container down on the ground. So synchronising the equipment and the interplay within the whole system, ideally so that everything runs in an optimised way too, that was the biggest challenge for the IT.

And then came the first test ship. Can you remember how the test went?

Martin Schubring: Oh yes, we can remember that very well. It was a 24-hour test, in which the whole system had to load and unload containers from a test ship. And we managed a total of 48 containers. That sounds great today, it would be close to the world record. Except that we didn’t manage 48 containers an hour, but in 24 hours. We started off somehow and with the first test ship nothing worked at all. Then seven or eight containers were moved, then something more serious went wrong and nothing happened for hours. I well remember the night of this 24-hour test. When you went into the office it was dark. And you had to be careful not to keep bumping into people’s feet, because some of the colleagues were stretched out on their desks and having a nap.

Ulrich Spindel: And between April and June we had six of these 24-hour tests. The last one was just before the first commercial operation – two days, I think.

And then you were ready for the inauguration on time. I can remember seeing photos with lots of coloured lights. Were you there too?

Martin Schubring: Of course we were. And the best thing was that we sailed there in the Cap San Diego. Then there were the illuminations, the fireworks and a few test containers, long banners and of course a big party on board.

Were the IT people also there to celebrate, as part of the party?

Ulrich Spindel: Yes, we celebrated too, of course. Not everyone will have been right on site for the party, but we celebrated too.

It certainly helped HHLA to cope with what was really massive growth in container volumes. It’s been 20 years since the CTA was opened, and much of the equipment is still operating. We have heard that the IT worked out well. So where do we go from here? Does the equipment have to be replaced at some point? Is there maybe better software nowadays, which has to be installed? Or can you say, the whole system is rock solid and we can carry on like this?

Martin Schubring: Both, in fact. The whole system is rock solid and we can carry on like this. Normal wear and tear means that we now have to start replacing the handling equipment. We’ve already done that in the AGV fleet, where almost all the vehicles have been replaced now. There were two reasons for that. The first is that the equipment just wears out. Secondly, we went a step further and replaced the diesel engine. That means all the AGV in service now are fully electric, battery-powered. The next assets up for replacement are the rail gantry cranes and above all the container gantry cranes. High-capacity utilisation at the CTA over the past 20 years – which is a tribute to the system! – means that the steel used for the gantry cranes has reached the end of its working life. Steel constructions wear out and so we are now starting to replace the container gantry cranes. That will take place over the next 6 to 8 years, as we install new, and also bigger and more modern cranes.

Ulrich Spindel: In IT we have kept renewing things successively over the 20 years. What has really proven itself, and is still running, and will continue to run in the years ahead, are the control systems. They were a completely new development, precisely tailored to the needs of Altenwerder. So we now have a mix, a combination of systems that have essentially been there since the beginning and new ones that have been added.

It was fascinating to talk to you. Thank you so much, also for all your work building the CTA and for all the sleepless nights.

Ulrich Spindel: Thank you for the opportunity to revisit those times.

That’s it for today, listeners.