What operational, planning-related or administrative tasks does it make sense for AI to help with? What effect could this have on old and new job profiles in the port environment? Will ships be driven autonomously in the future? Nils Kemme, Managing Director at HHLA's consulting subsidiary HPC, has been dealing with these questions for a long time.

Artificial Intelligence in logistics

What is AI all about, how does HHLA benefit from this technology and what are the advantages and disadvantages?

Dive into AI in logisticsThe audio part is only in German available, below you will find the English transcript of the entire interview.

In today’s HHLA talk for our magazine, we are discussing artificial intelligence in the port. To many people, artificial intelligence, or AI for short, remains a technological field that is still shrouded in secrecy. Robots with superhuman powers like we see in science fiction films are a familiar cliché. In reality, the use of AI and the opportunities that come with it are far less spectacular. Nevertheless, artificial intelligence is revolutionising many areas of work, including within logistics and the port. And if there’s anyone who knows about port handling using artificial intelligence, it’s Dr. Nils Kemme. He designs and optimises container terminals around the world in which artificial intelligence, as it now also does in countless other areas, plays a key role. But before we get to that, please tell us a bit about yourself.

With pleasure. My name is Nils Kemme. I originally studied and got my degree in business administration, for which I specialised in operations research, a science at the interface between informatics, mathematics and economics. From this starting point, I was lucky enough to begin my career in the port upon completing my course of studies and to write my thesis on the subject of AGV fleet optimisation whilst based at HHLA Container Terminal Altenwerder. I subsequently moved to the Tollerort terminal and then to HPC, HHLA’s consultancy subsidiary. After two years at HHLA and HPC, I returned to the University of Hamburg to begin working towards my doctorate, once again specialising in the field of operations research, and thus in something of a key area of application for artificial intelligence. While there, I earned my doctorate in the optimisation and planning of container terminals before once again returning to HHLA’s consultancy subsidiary, HPC, where I have been now for around nine years.

Dr. Kemme, if we are to throw aside the idea of the super-intelligent talking robots that we see in Hollywood films, are there specific ways in which artificial intelligence is defined, depending on the area of application in question? How would you define AI in the most general terms?

It is actually very difficult to offer a general definition, because the term “intelligence” is in itself hard to define. For us as humans, climbing a flight of stairs might be an incredibly easy task. For a machine, however, it is a highly complex act involving complicated movements. However, one could say that it is about replicating human decision-making structures within AI.

Is it possible to clearly distinguish between the concept of “AI” and the technical term “machine learning”, that is to say, a computer program capable of learning that controls automated work processes? This is a term which now crops up frequently in discussions around this topic.

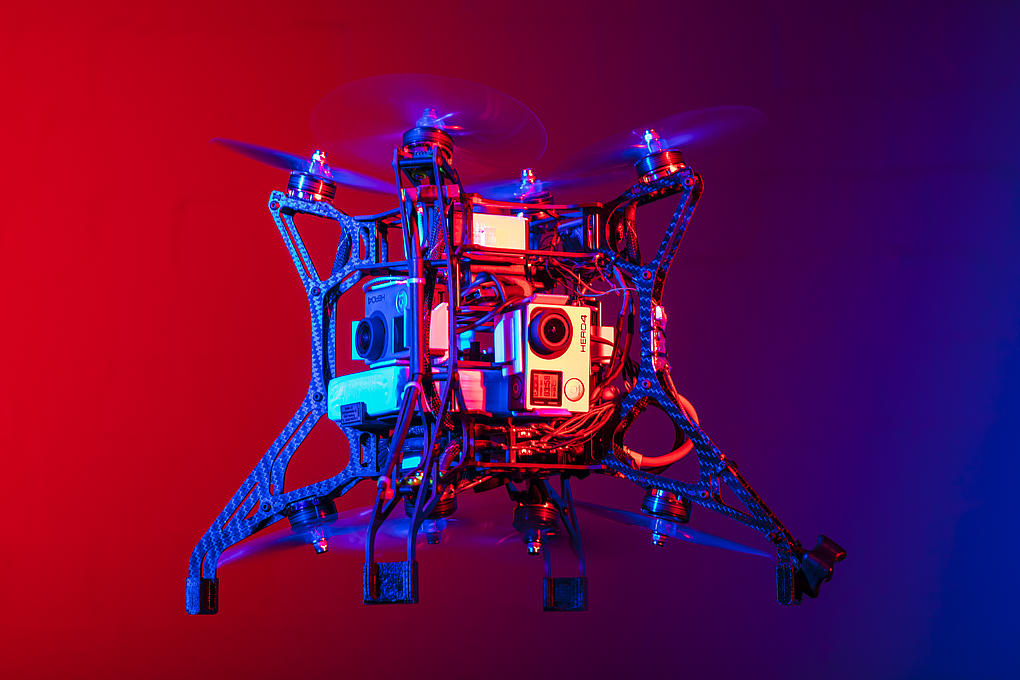

Artificial intelligence can be more narrowly defined by two terms: autonomous and adaptable. If a machine is autonomous and adaptable, then that is thanks to artificial intelligence. In principle, adaptability means the ability to react independently to a changing environment. If we look at its application within image recognition, for instance, it is important that the machine is able to react to a changing environment, such as weather conditions or different backgrounds. This then enables it to correctly recognise the image, like a “30 zone” sign, for example. And this is exactly where machine learning comes into play. Machine learning is an adaptable system and, in this respect, a part of artificial intelligence as a whole.

Before we broach the subject of the special area of application that is the port: could you name for us a few applications of artificial intelligence elsewhere in the business world? Including examples that are perhaps so well hidden or already so commonplace that we are barely even aware of them in the course of our day-to-day lives.

In my opinion, the most well-known applications, at least for anyone who owns a mobile phone, are voice assistants like Siri or Alexa. Artificial intelligence has to be used here in order to allow speech patterns to be recognised. Other areas of application are autopilots in self-driving vehicles or even personalised advertising, that is, when you once again find yourself wondering how the computer knows to present you with such well-tailored advertisements online.

As a layman, one does not tend to associate AI with the word “ports” as often as one might do with other business sectors. One thinks: container handling? That’s all about heavy boxes and heavy equipment. What use is an intelligent software solution there?

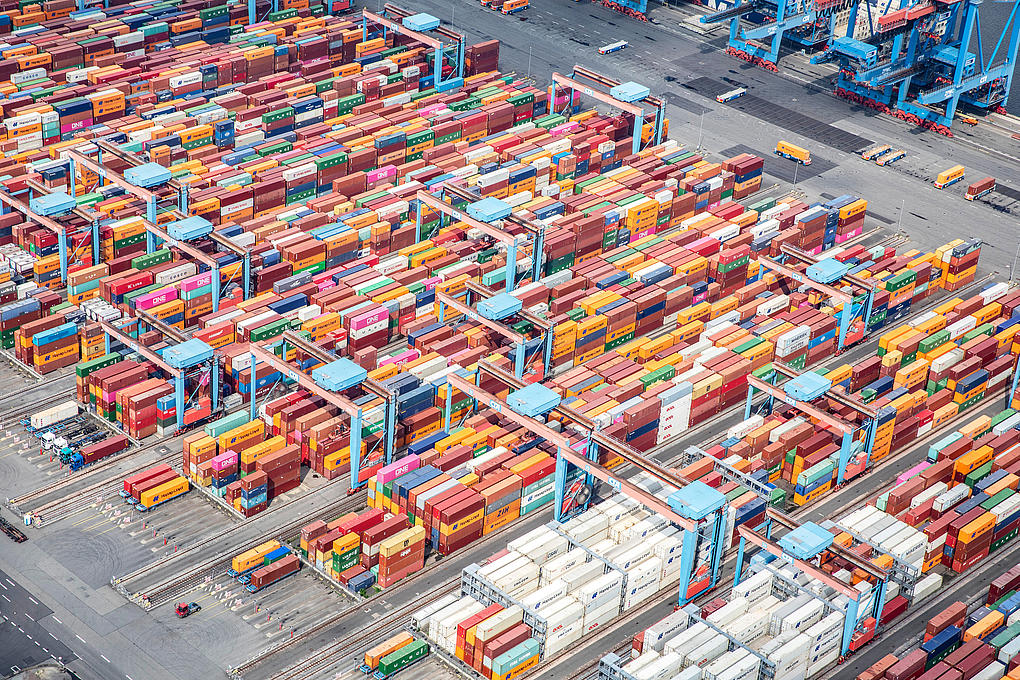

At a container terminal there are, of course, thousands of containers, many vehicles, many container gantry cranes, storage cranes – all objects that require planning. Which piece of equipment is responsible for which tasks, where has each container been placed in the yard? These are all planning tasks that can be done by artificial intelligence. It can also be used to improve the quality of the data used for the planning decisions, such as how long a container stays in the yard. Another area of application is predictive maintenance. Artificial intelligence helps us to predict when a piece of equipment is likely to fail and thus to implement the maintenance cycles, or rather, the repair work, that will prevent this from happening. In this way, the equipment undergoes “just-in-time” maintenance, so to speak, before it actually fails. At Burchardkai container terminal, we are testing the use of predictive maintenance to predict the remaining service life of cables on the container gantry cranes. These cables help to lift the containers off the ship. By predicting how much longer these cables will last before tearing or breaking, we can achieve two things. Firstly, we can arrange for the cables to be replaced at times when the container gantry crane is not required for use. This therefore prevents any negative impact on the handling of the ships, allowing this to, in principle, proceed more smoothly. Another advantage is that we do not end up replacing undamaged cables, which allows us to continue using them and therefore extend their service life. Any delay in the handling of a ship results in major subsequent costs for HHLA. And if we are able to extend the lifespan or service life of a cable and further delay maintenance work, we can then prevent spare parts being used unnecessarily, which results in direct cost savings.

HHLA’s state-of-the-art container terminal, CTA in Altenwerder, is another location where artificial intelligence is used. AI is employed there for a wider range of responsibilities. Not merely making predictions, as in the example you just gave, but rather making its own decisions through the use of software. What is going on here?

At CTA, algorithms are used, or, to be more specific: rule-based algorithms. In principle, these make all decisions relating to the automated equipment. For example: which container is to be placed at which storage space, which automated transport vehicle is to transport which container from A to B, which route is to be taken? At this terminal, all these decisions are made by algorithms. In a broader sense, these algorithms can also be regarded as artificial intelligence.

Are there legal aspects to all this too? If AI is allowed to make its own decisions, which are then implemented in the real world, could it, for example, be held liable if the decisions subsequently prove to be wrong and result in damages?

The AI itself will not be held liable in any event. It would ultimately be the people behind the AI. To be more precise, I mean that no additional legal provisions are required specifically for AI, as the law in its current form already includes extensive liability provisions for damages incurred through the use of technical equipment or software. Ultimately, the company and management behind the AI are liable.

As a HHLA subsidiary, HPC advises ports and logistics companies around the world. Does this advice also concern the use of AI in many places?

Absolutely. The significance of AI within the international port environment is growing rapidly. As mentioned at the start, many fields of application have been identified in recent years which are also already in use or being trialled by other major terminal operators. This is the case for large global terminal operators such as APMT in the Netherlands or Dubai-based DP World, for instance. The operators are also looking at very similar fields of application to those of HHLA. Predictive maintenance is often at the forefront of these efforts. This is not merely limited to the crane cables, but also applied to the equipment as a whole. These applications also include the improvement of data quality and the container’s dwell time in the yard, for example. And some terminal operators are also already looking at use cases for decision-making with the help of artificial intelligence.

In light of your experiences around the world, what are the greatest challenges faced in the case of projects involving artificial intelligence in logistics?

First and foremost, it has to do with data availability. The data needed to train the AI is usually available somewhere at the terminal. The way in which the algorithm used by the AI is trained forms the basis for its subsequent application, which means that the more data that is available, the better the artificial intelligence will function. However, it is often not possible to locate this data and many systems must first be combined with one another to allow this to happen. This represents the bulk of the work involved in developing functional applications of artificial intelligence for terminals.

Looking beyond the actual handling of containers and its associated logistics, what other maritime applications are there for artificial intelligence, applications which are perhaps still in the research or development phase?

If we stay within the realm of maritime logistics, and within shipping more specifically, then there are specific applications such as the navigation of ships, namely, the weather-optimised navigation of ships. This is something that is already underway. The shipping company OOCL, for instance, is working with Microsoft to optimise routes for its ships using artificial intelligence. By using tailwinds and avoiding areas of poor weather, they could save more than 10 million dollars a year. Other applications in shipping are, of course, energy consumption, or rather its optimisation. This is closely tied in with route optimisation and, increasingly, collision avoidance. And when we talk about collision avoidance in regard to ships, then the next logical step is to also start thinking about autonomous ships: entirely unmanned ships which are controlled exclusively by the computer or by artificial intelligence. This technology is used in Norway, for example, where Yara Birkeland has been sailing back and forth between two ports since last year.

There is another key area that we still need to discuss: the relationship between human labour and machine-assisted work within the port. And so we come to the frequently asked question: will AI replace or make redundant increasing numbers of jobs in the future?

There no easy answer to this question. What I can say is that AI will increasingly take over operational, planning-related and even administrative tasks, which in turn means that manual tasks, manual activities, simple activities will also disappear. At the same time, there is a growing need for qualified specialists in AI technology. Not just for software developers or equipment suppliers, but also for roles within the port, for people to monitor and manage the equipment.

You have already addressed the need for more AI solution specialists. What specialisations are there, and how are these specialists, who are in such great demand worldwide, recruited to work at HPC or HHLA?

There are only a few specialised courses of study for artificial intelligence itself. Generally these form part of a degree in informatics, mathematics or even engineering. One therefore acquires real-life competence in the field of artificial intelligence through practical experience. This occupation is known as that of a data scientist. As mentioned several times: data forms the basis of artificial intelligence. As such, a data scientist is the individual who understands this data and even uses artificial intelligence as a tool for analysis. As a data scientist at HHLA and its consultancy subsidiary HPC, one has the opportunity to help shape a robust and vibrant industry in an innovative and dynamic environment, unlike in other industries such as insurance or banking, where the use of artificial intelligence is also growing.

What do data scientists, or even you personally, need the most in order to do your job? A deep methodical understanding of AI or a comprehensive knowledge of its area of application, ports and logistics?

A healthy understanding of artificial intelligence is without a doubt a necessary prerequisite, as this is what enables us, as experts, to make decisions regarding the suitability of artificial intelligence for specific areas and applications. But industry knowledge, and in this case knowledge of the port environment in particular, is of vital importance. Only then can you also know which data is required, which influencing factors you need to monitor, in order to create a successful AI application.

Would it be correct of me to summarise our conversation by predicting that even in 20 years, there will not be any humanoid robots marching through the port and issuing orders? But that collaboration between human and artificial intelligence will increasingly become the norm?

I should think so. Autonomous equipment and vehicles will increasingly become the standard within the port. Artificial intelligence will also assume increasing responsibility for decision-making and administrative tasks. Simultaneously, we will also see people continuing to play a key role in the port. There will be applications, within both the operational and administrative divisions, which are carried out by human beings. This increasingly includes controlling and monitoring activities.

Well thank you, Dr. Kremme, for this exciting and entertaining conversation. I, for one, am happy that this interview could be conducted the old-fashioned way, with human intelligence. The next HHLA talk will focus on modility. Not yet familiar with this start-up? Then remember to listen in next time, and make sure that you also subscribe to our newsletter by visiting www.hhla.de/Update.

Pioneering and digital

The pace of global changes will continue to accelerate, so HHLA is preparing itself for the world of tomorrow. What is the company doing to tap into profitable growth areas? Which new technologies are being tested or are already in use?

Learn more