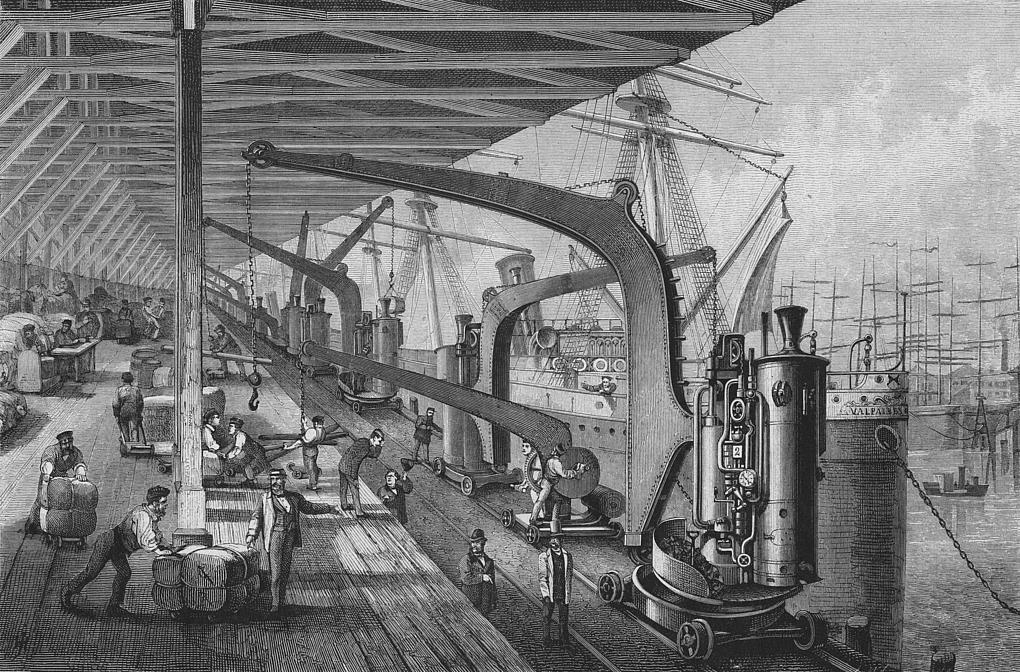

In the 1970s, the container revolutionised the shipping industry and port handling at such a fast pace that the bureaucracy associated with handling couldn’t keep up. Before then, accompanying freight information was still documented on paper forms which were passed through all handling stations from seaport forwarders to quay operators, cargo inspectors and shipbrokers. Whole piles of documents were transported back and forth between the companies involved, often in courier vehicles.

This all came to an end in summer 1983 with the cross-company DAKOSY data communications system. HHLA was also a part of the system from the beginning since the integration of the companies involved made it possible to quickly and reliably exchange data on seaborne cargo handling at the Port of Hamburg.

“EDP” became indispensable for port operations

Now computers delivered key identification data for cargo to the terminal at the push of a button. Processing and billing of the transaction were aligned with the speed of the physical handling of the goods. By 1987, 136 port companies and institutions were connected via DAKOSY. “Electronic Data Processing”, as it was called at the time, became indispensable for port operations. As a result, increasing numbers of EDP specialists and computer scientists found employment in the port.

The driver’s cabins of the long-legged straddle carriers for container transport at HHLA Container Terminal Burchardkai were already equipped with visual display units and connected to the computer centre by radio in 1984. A world premiere! Now the position of every single container at the terminal could already be determined and transmitted during the journey, leading to quicker handling.

Dockers and employees alike quickly adapted to the new technical developments. Some who had previously used basic technical equipment to move goods, or who had carefully compiled freight lists using a pen and ruler, were trained to drive the new heavy machinery. Others trained for newly created jobs such as that of the maritime goods inspector.

New jobs came and others disappeared in the port

This skilled occupation that first emerged in the mid-1970s was a combination of former jobs carried out at ports, primarily the positions of quartermaster, tallyman, port inspector and other jobs related to port controls. Starting in 1975, vocational training to become a maritime goods inspector was regulated by the state through the Vocational Training Act, and this replaced the former professions.

However, the initially modern profession of maritime goods inspector also changed in light of technical progress. In 2006, vocational training was adapted to reflect the changes in port operations and from then on, HHLA began to train experts in port logistics.

HHLA has consistently remained at the forefront of technical developments. For instance, starting in about the mid-1990s, the locations of containers at Burchardkai were determined using a combination of the newly implemented GPS satellite positioning system and a gyrocompass on board the straddle carriers. This was followed by the satellite-assisted optimisation of drives through the container yard in 1997. Since then, computers locate the vehicle with the shortest distance to move a container between the quayside and the yard.

In 2002, HHLA opened its most modern container terminal in Altenwerder. Container terminal CTA became a showcase for the next major innovation in handling operations: the Automated Guided Vehicle (AGV). These automated, computer-guided container transporters replaced human-driven straddle carriers.

A central server is informed of the traffic in real time via a network of approximately 15,000 transponders that are embedded in the ground. This determines the optimal route and the course of all AGVs. The AGVs are used on the route between the berths and the similarly automated storage blocks where the containers are stacked. Today, almost 20 years later, AGVs are learning to drive with green energy. HHLA will convert the entire fleet from diesel to battery power by 2022.

Mobile data communications, satellite positioning and other innovations at Burchardkai

What about the people who used to sit behind the wheel?

If self-driving transporters and yard cranes also catch on at the other terminals in the port, the question arises: What happens to the drivers? There is no easy answer to this predicament. The main priority will lie in helping employees to further their development and working with them to open up new perspectives for their careers.

Automation is also continuing unabated in other areas of the port. For example, all container trucks that arrive at Burchardkai travel through a portal equipped with cameras and sensors to automatically record the basic information on the steel boxes and upload this to the system. This was formerly the job of up to five gate checkers. Artificial intelligence (AI) can perform this job more precisely and save the truckers time. However, people still have to monitor their not entirely error-free AI colleagues.

In retrospect, one thing is clear: If the Port of Hamburg had not gone full steam ahead with modernisations since the mid-19th century, it would not be the competitive international port it is today. It might have ended up like London, the largest port in the world in its day, where the last dock closed in 1980.

The port planners for London elected to construct a dock port with enclosed channels, a concept that had already been rejected in Hamburg in 1862 in favour of the open tide port, which was revolutionary at the time. Over a century before the arrival of containers at the Port of Hamburg, this decision set the course for future success. This progressive approach will continue to help the Port of Hamburg to reap the rewards of the future revelations in logistics.

Milestones in Port Logistics

Technological breakthroughs are multiplying productivity in the port: from electricity to containers to the growing data flows.

Read more